The 2017 Alder / Third Sector culture survey: charities facing significant exposure to reputational damage.

The last two years have been among the toughest ever known for charities, with controversies over executive pay, governance failures and data-sharing dominating the headlines.

Yet despite high stakes and an apparently strong consensus on the need for change, the 2017 Alder / Third Sector cultural health survey reveals many organisations are still exposed to significant reputational risk.

At a time when regulators and politicians have been making clearer than ever that the buck stops with trustees, perhaps the most significant gaps relate to the boards engagement with the organisation they are supposedly responsible for.

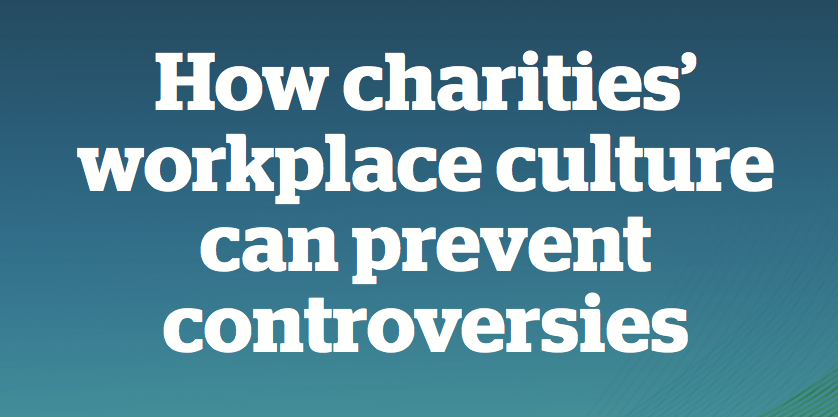

For instance, of the 382 charity leaders we questioned, 32% said their organisation did not review their trustees performance in any way. Whats more, almost a quarter (24%) said their trustees would not know if there was a poor workplace culture at the charity. These are surprisingly large figures, suggesting a significant exposure to risk.

Trustees may be unremunerated and part time, but they fulfil a vital governance role, and the way they execute it is often the difference between a strong reputation and a PR disaster. So it is essential they have the right degree of visibility of how the organisation works so they can identify red flags and take action on any emerging cultural problems. They should also ensure they get good feedback on how they work themselves since their own performance is critical to creating a positive culture.

It is not difficult to see what happens a charitys culture and governance go awry. The collapse of Kids Company is a sobering case study, but is one people should be wary of dismissing as an aberration that could never happen to them.

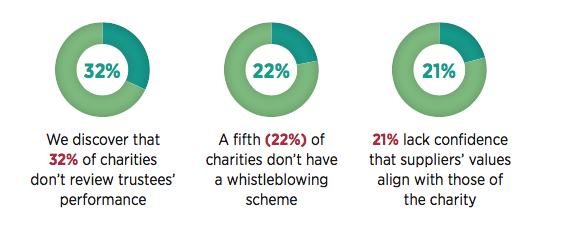

Thats because, while major cultural problems are always easy to identify in hindsight, spotting the early warning signs is not that easy when you yourself are part of the picture. Fortunately there are structures and processes that can be entrenched to minimise risk. A whistleblowing policy is a good start, though 22% of our respondents said they didnt have one at all, while a further 35% had one which hardly anyone knew about.

Of course these figures can be inverted and an argument made that good practice is fairly widespread. And indeed some indicators of an organisations culture such as the quality of internal communications are rated well, with 74% of respondents saying they were either good or excellent at their place of work. But the question remains why more attention is not paid to some obvious weakspots. For instance, around a fifth (21%) of respondents werent confident that their suppliers values aligned with their own. Given the public interest in and numerous media stories about problems in charities supply chains this is a clear area for attention.

So what should charities do?

The link between poor organisational culture and PR disasters is clear. So the first step is to analyse exposure to risk. There are numerous indicators of whether a culture is becoming toxic, from how KPIs work to attitudes to health and safety and the quality of training. The effectiveness of communications, the engagement of trustees and external reputation all these are relevant too, and are things that can be measured and therefore improved. When a proper 360 degree picture of the charitys health has been established the risky areas can be examined and plans for improvement enacted. With a concerted strategy, risk can be severely reduced, if not eliminated.

All charities in common with all companies, large and small have room for improvement. Those who think they dont probably have the biggest problems of all.

For a copy of the full report, please email [email protected].